02 October 2013

Dear Family, Friends, and Colleagues,

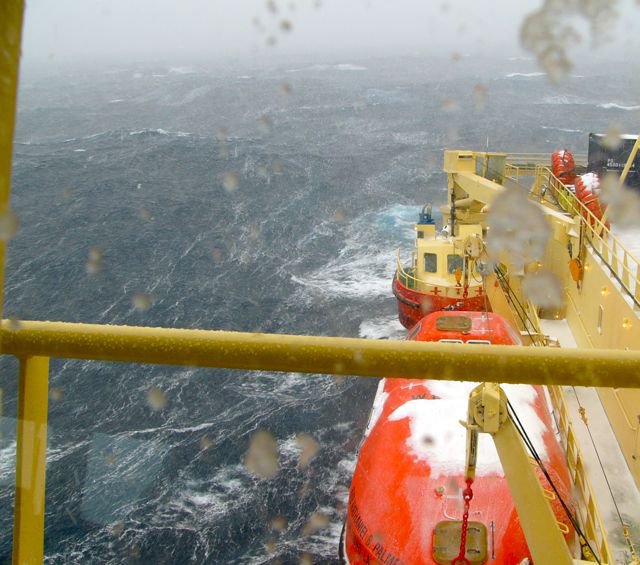

One of the inescapable aspects of working in the Southern Ocean is storms - both the ones that hit directly and the more distant ones that generate the long, rolling waves known as swell. The Southern Ocean may be the stormiest large-scale environment on earth - I don't know that for certain but it feels that way. Big low pressure systems (storms) develop and evolve to circulate around Antarctica in a steady parade. Our mote in the ocean - the Nathaniel B. Palmer - has been hit three times so far by storms with winds well over 40 knots (equals 46 statute miles/hour), plus the ship is always affected by swell (sometimes quite large) propagating from distant storms. We can work in wind and swell to a degree, but we have already had more than 77 hours of down time when the seas were too rough to work.

As part of our cruise support, we receive weather forecasts customized to our location. In the old days such forecasts were next to worthless, but with the advent of weather satellites and computer models, we get a day or two warning of each storm. So what do we think when we hear a storm is forecast to affect us soon? Well, officially it's "get as much work done as we can and get everything tied down", but unofficially it's also "get to the laundry before the storm hits", because the laundry machines must be shut down during storms in order to avoid damage to them caused by ship motion.

The Palmer rides the storms well. The captain and his officers choose a heading and slow speed that will provide a reasonably good ride, and try to judge when to head back to the next station just in time for the seas to have improved post-storm to the point where we can go back to work. We have work to do, but the pace definitely slows with no new samples to analyze. Some people suffer more than others from seasickness, though the fortunate majority of us have now adapted to the ship's motion in stormy seas.

The biggest storm, with a long spell of sustained winds over 50 knots, caused some damage: a storage van on the fantail was partly caved in by a wave. A photo frame from the ship's stern video camera (See left) shows a large wave breaking over the fantail. You can see why we do not go out on deck in heavy seas or storms!

I have been asked, "how much 'bad weather time' did you allow when you planned the cruise?" The answer may surprise you: none. With the cost to taxpayers of a research cruise like this running in the $100,000/day range, one cannot justify extra funds for contingency expenses. And, anyway, this cruise is already near the Palmer's maximum duration at sea (mostly determined by fuel) for our type of work. What I do have is a maximum science plan that will accomplish all objectives within the allotted time, and the responsibility to make the best cuts to it (if needed) at the best times so that we accomplish our highest priorities while still ending up at the last planned station shortly before the time, barring emergencies, that we must head to port.

The other day, while we were waiting out a storm, I noticed we were entering a field of rotten first-year sea ice leftover from the summer melt. Aha! I asked the gang to prepare the rosette and alerted the deck tech and bridge: I knew that in the ice the large seas would be damped down and we could do our station. The mate on watch kept us in a small patch of open water in the midst of the ice field, and everything worked out great. Meanwhile we passed by some crabeater and leopard seals hauled out onto the ice (photos attached - See above right and below). [Quick, how can you tell, when you see a seal on the ice, if you are in the Antarctic or, instead, the Arctic? If you can come right up close to the seal, you are in the Antarctic, and if the seal dives in the water at first sight of you, you are in the Arctic. The difference: polar bears (an Arctic-only predator).]

We already have some exciting science results: significant changes since 1992 in seawater temperature and salinity along our transect of stations NE from Cape Adare. We'll soon send early results to the science team ashore to whet their appetites.

The food is great (some of us already fear we may be getting great ourselves), and all hands (ECO, RPSC, and science guests alike) enjoy the friendly and productive atmosphere on board. We may get a tiny bit frustrated during the storms - we came here to work, after all - but we are a happy bunch.

All is well aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer.

Jim Swift

Chief Scientist

NBP-1102 / S04P

Nasty weather (Swift)

Nasty weather (Swift) Wave breaking on deck (NBP)

Wave breaking on deck (NBP) Leopard seal (Swift)

Leopard seal (Swift) Cargon van damaged by waves (Swift)

Cargon van damaged by waves (Swift) Crabeater seals (Swift)

Crabeater seals (Swift)